From Pressure to Vibration—The Event of a Thread

Emma Fitts wall hanging installations, from Pressure to Vibration 2017

(NB: this Blog post was originally published in July 2017 and is now archived here, from my previous website)

I was in Wellington during the April school holidays so took a bus up to the Dowse to check out From Pressure to Vibration – The Event of a Thread, curated and featuring work by Emma Fitts. It was a multi-layered celebration of textile themes including history, conceptual art, archival studies, traditional craft and architecture. In other words, a Big Deal. I was so lucky to catch this!

The concept is this. Fitts has unearthed a spectacular archive of textile art held by the Dowse, and what an archive it is. She’s organised these works according to some of the guiding principles used at the Bauhaus school of design: pressure, pricking, rubbing, pain, temperature and vibration.

Then, combining the role of artist and curator, Fitts has woven her own large scale, newly created architectural panels throughout the older works, also based on these principles.

She’s given us a heady brew of history, craft and industry. I’ll break it down by the same Bauhaus categories Fitts has used to categorise her archical selections.

Judy Patience, Wall Hanging, 1974. Wool, Brass

1. Pressure: architecture

Judy Patience’s impressive large-scale weaving was the winning entry in the 1974 design competition for the Dowse’s entrance foyer. Now, personally, I often find the 1970s slightly hard work, with a recurring tendency of too much of everything. But I can see in Patience’s piece the perfect antidote, then as now, to the overwhelming architectural environment of concrete, steel and glass. Its textured lines and angular pattern-pockets reflect and enrich the space it was designed to inhabit. The vibrant pops of colour woven three dimensionally over an olive background sings the very best of the decade which brought me up. I find it an unbridled joy.

Judy Patience, Wall Hanging, 1974. Wool, Brass (detail)

2. Pricking: modernism

Loom weaving increased in popularity in Aotearoa in the 1950’s and 60’s where cottage industries where rife and sophisticated domestic products came out of numerous spinners and weaver’s guilds across the country.

For Margery Blackman and Judy Patience the German American textile artist Anni Albers, who headed the Bauhaus weaving workshop (taking over Gunta Stolzl in 1931) had a significant influence. Her books, On Designing (1959) and On Weaving (1965), highlighted weaving as a mode of modern design. Albers was the first designer to have a one person exhibition at the Museum of modern art in New York in 1949, making her one of the most important designers of the day. The exhibition travelled to 26 museums in the US and Canada.

But it is impossible to talk about New Zealand textile art without also talking about the rich craft, skills and culture of raranga: Maori weaving. Margery Blackman has done a vast amount of work analysing and documenting western European and Maori weaving practices. Fitts’s inclusion of Blackman’s imposingly large work From Aramoana (1981) is a fitting tribute to this research.

The work itself was created in protest in the 1980s when Muldoon’s government tried (and failed) to build an aluminium smelter at the tiny, coastal Otago village of Aramoana. But “aramoana” has another meaning, more evident here: it’s one of the names given to the taniko panels that adorn the walls of wharenui. Literally, it means pathway to the ocean.

It’s hard to think of many examples which so artfully and subtly blend the multitudinous voices of tikanga Maori with western art practice.

Margerey Blackman, From Aramoana 1981 – 1982, wool, cotton, linen, silk mohair

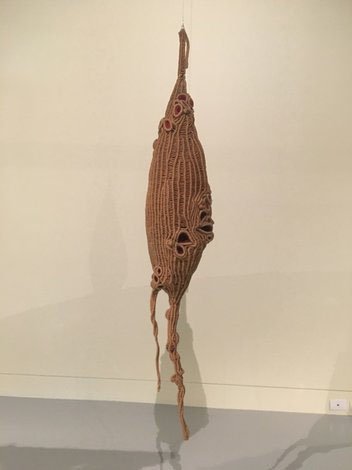

3. Rubbing: fibre art

Joan Calvert and Zena Abbot’s work from the 1960s and 70s is exemplary of the widespread growth of sculpture across all mediums at that time. Whether it was because representational painting had reached the end of its tether, or whether it was some new-found freedom the art world found in the third dimension, who knows? But the work of both these artists is highly sculptural, and very free.

Joan Calvert is quoted as saying “I prefer to work in a spontaneous manner, knowing initially the atmosphere or feeling I wish to create but not altogether how I am going to achieve it”. That intuitive approach is clearly evident in 3D Form.

Joan Calvert, 3D form, 1975. Wool, fibre, plastic

Zena Abbot also pushed the boundaries of textile weaving as an art form. Her work Roving plays on little known etymologies of the word itself. Roving can not only mean to wander, it is also a twisted bundle of fibre, and – as a verb – another word for spinning fabric.

Zena Abbot was an influential weaver in New Zealand, inspiring many through her workshops and weaving business.

Zena Abbott, Roving, 1977. Sisal, rope

4. Pain: story-telling

Anyone who knows me knows that I’m keen on this idea. My interest in the interplay of text and textile goes back to my childhood diaries and doodles. So it’s pretty damn exciting for me to see this idea reflected on a large scale in an exhibition like this. And yes, I like the matching. Story telling can hurt!

This part of the show – for me – lay heavily in the hands of Fitts as curator.

Four traditional woven pieces: a kete, a platter, a bottle and a cylindrical basket sit elegantly pinned to the stark white gallery wall. Their artistry and meticulous crafting much in evidence. In a few deft curatorial strokes, Fitts brings their significance to life:

O te wananga, where three baskets of knowledge are brought to Earth

Te kete tuaui (sacred knowledge)

Te kete tuatea (ancestral knowledge of memory, ritual and prayer)

Te kete aronui (life’s knowledge)

In a show overflowing with narratives, it seemed fitting that the section devoted to “story-telling” should trace back to the fundamentals of the sacred, the ancestral and the living.

Erenora Puketapu-Hetet. Kete Pingau, 1983

Ruth Castle Platter, 1995

Ruth Castle, Cane bottle, Cylindrical basket, 1995

5. Temperature: textile industry

Textile and industry have always had a close relationship. In fact, the industrial scale of textile production is precisely a function of the importance of textiles in human life. It’s all very well to enthuse over beauty, but textiles need industry to do their job. And indeed, it is largely around the use of raw textiles in the industry that has caused this terrible leap into the toxic issues we face today.

Fitts has used this paradigm to display the wide range of weaving techniques of Wellingtonian Sheila Reinan, with a large range of samples spanning the years 1980 – 2005. Through her own commentaries, Fitts contextualises Reinan’s artisanal craft with the commercial craft of the Petone Woollen Mill. Closing in 1968 after almost a century, the mill thrived on the skills and knowledge of hundreds of women, a lot of them immigrants who’d learned their skills in the mills of the UK.

Reimann started on a small table loom in 1980, ultimately graduating to a 48 inch Sunflower floor loom, specializing in scarves, shawls and throw rugs, working with colour structure and texture and often dyeing her own yarn.

The hand loomed pieces on display in this exhibition are exquisite examples of a range of techniques. Reimann’s later works incorporated unwoven areas with woven, and by using differential shrinkage from washing she developed the corrugated and bubble effects that became her signature style.

Fitts quotes Reimann:

“It seems to me that the history of the world can be seen through cloth. In today’s ‘throw-away’ society, with so much mass-produced cloth available, I feel that handmade cloth provides a link with that past… and its unique blend of mathematics and art.”

Selection of weaving samples with their pattern notes by Sheila Reimann.

6. Vibration: Raranga

From the pressure of architecture to the vibration of Raranga. While it’s impossible to talk about Aotearoan textiles without talking about raranga, it’s equally meaningless to consider raranga – or any textiles – outside of the context of applied arts. Some people get a bit sniffy about crafts. But within tikanga Maori, the traditions of raranga are awe-inspiring in their holistic approach.

The woven hieke (rain capes) of Whiona Epiha and Philpa Devonshire are high examples of a traditional practice which has been passed down orally by generations of women for many centuries.

And since the very word “curate” means “to preserve”, Fitts has done well to let these traditional works speak for themselves.

Whiona Epiha, Te Ahi Ka, 1994, harakeke, neinei, pingao, jute, 1994

Philipa Devonshire, Ki a Hinemoana 1994, kiekie, pingao, pukeko feathers, jute, processed fibre, dye.

Waiwhetu weaver Erenora Puketapu-Hetets works are made using taniko a weaving technique. The text that features on the cones reads:

E ara ra, Eoho (to stir and wake up):

Maranga (to get up, new opportunity):

Kokiri (to advance and move forward on a number of fronts);

Iwi, te tai, tu tangata (for people to be upstanding and proud)

Puketapu-Hetets is quoted "I enjoy pushing the boundaries as I am certain many weavers of the past did. I enjoy the freedom to make statements about current issues that affect our Maori people. Weaving is a vehicle to reflect my views, my thinking, my feelings. The weavings reflect our Tupuna, our Iwi, Hapu and Whanau which is an essential part of my being"

Erenora Puketapu-Hetet, Tuku Mana Whakahaere, 1990, waxed linen thread.

7. Pressure to vibration: Emma Fitts

Fitts’s works were the only ones in the show that were not archival (whether or not they are now, I don’t know). Extraordinarily large, even by textile art standards, giant panels of felted wool, some with overlaid patterns of fabric taken from Bauhaus designer Lilly Reich’s dresses, they hung from the ceiling and curved their way through the galleries, both connecting and dividing the six Bauhaus-inspired zones.

Fitts replicated the layout of the two Bauhaus designers Ludwig Mies van der Rohe and Lilly Reich’s installation for a fashion industry exhibition in 1927, which doubled as a café called Cafe Samt & Seide.

Emma Fitts wall hanging installations, from Pressure to Vibration 2017

Why Bauhaus? The German art school of the 1930s still has much to offer textile design, art and business. The reason why - again – is precisely because textiles and business are inextricably linked.

Fitt’s exhibition provided a welcome moment of brilliant illumination amid an industrialised reality where brands carry more value than quality, and the cheaper the better.

I hope I do this show justice it deserves. I have had to leave a few textile pieces out of this blog, as the need for some brutal editing was required! This exhibition has certainly pushed a few buttons in me.......so watch this space for the next blog.

(Blog post originally published in 2017 and brought over from my previous website!)